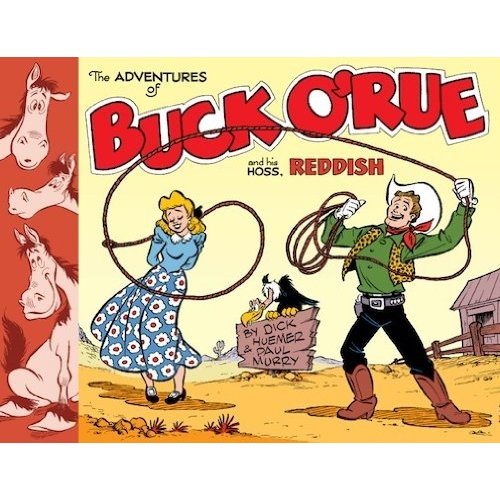

The Adventures of Buck O’Rue and His Hoss, Reddish

Authors: Dick Huemer and Paul Murry

Publisher: Classic Comics Press

ISBN-10: 0-9850-4991-X

ISBN-13: 978-0-9850-4991-1

A confession: I requested a review copy of this book to solve a sixty-year-old minor mystery for me. When I was a child and a teenager in the late 1940s & ‘50s, my family got the Los Angeles Times and the Los Angeles Examiner, and I devoured every comic strip in them. But there were other newspapers in Los Angeles, and they had other comic strips. I only saw them infrequently, but one strip that intrigued me was Buck O’Rue, a burlesque Western in the L.A. Mirror, because I recognized the cartoonist’s style as the same artist who was drawing the Mickey Mouse adventure serials in the monthly Walt Disney Comics & Stories comic book. When I grew older and talked with other comic-strip and comic-book aficionados and asked about Buck O’Rue, nobody had ever heard of it.

Now Classic Comics Press has published “The Adventures of Buck O’Rue and His Hoss, Reddish”, an “everything you could possibly want to know” handsome large (10.9” x 8.3”) 302-page trade paperback that contains everything about this obscure, short-lived comic strip. It was created by writer Dick Huemer (1898-1979) and cartoonist Paul Murry (1911-1989), two longstanding Walt Disney studio employees who had just been temporarily laid off. They created the Buck O’Rue strip together as self-employment, then ironically were called back almost immediately by Disney and given so much work that they did not have time to continue their strip. Huemer’s later Walt Disney work, mostly on the TV programs, included writing the Disney True-Life Adventures newspaper strip from 1955 to his retirement in 1973, while Murry spent the rest of his career drawing Disney-character comic books including those Mickey Mouse stories that I recognized. Buck O’Rue lasted from January 15, 1951 to December 7, 1952 when it was discontinued in mid-story; I was ten and eleven years old when I saw the few strips that I did.

In addition to the complete run of the strip (except for six daily strips that could not be found), this book includes publicity press releases written about it from Los Angeles to Toronto, photographs of Huemer and Murry, biographies of them (including caricatures by other Disney cartoonists), samples of their other work including pre-Disney cartoons (Huemer had previously worked at the Fleischer Studios in New York) and their other Disney assignments, and an essay by the son of Buck O’Rue’s distributor, the tiny Lafave Newspaper Features. Usually Classic Comic Press specializes in de luxe reprints of famous newspaper comic strips (Mary Perkins/On Stage, Big Ben Bolt, Dondi, etc), but in this case a classic collection of the Buck O’Rue strip was edited in their format by Richard Huemer, Dick Huemer’s son, and Germund von Wowern, a professional comic-strip editor.

For two humorists in 1950-‘51, the Western must have seemed the obvious subject to lampoon. During the 1940s and 1950, Westerns were one of popular entertainment’s favorite genres. There were the series movies with Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, Hopalong Cassidy, and many others, and the non-series movies starring A-list actors, exemplified by such as Shane and High Noon. There were the radio dramas like The Lone Ranger. There were comic books; practically every movie cowboy hero had his own comic book, there were independent comic-book publishers’ series like Timely/Marvel’s Two-Gun Kid, funny animals like Mickey Mouse and Porky Pig had frequent Western adventures, and there were even funny animal cowboy heroes like ‘Red’ Rabbit. In newspaper comic strips, there were Hopalong Cassidy, the Lone Ranger, and the Cisco Kid again.

But these were all played straight. Even the Westerns starring funny animals were straight-faced adventures. Huemer and Murry set out to parody this. Buckingham O’Rue was the acme of a cowboy hero; handsome, respectful to wimmenfolk, and ready to accept any gunfight duel although he always shot to plug his adversary’s gunbarrel or to deflect his bullets, never to maim, much less kill. Although he had a steady girl friend, the lovely Dorable Duncan, readers soon suspected that he cared for his horse, Reddish, and his shiny six-shooter Silver Sal more than he did for her. (This was over a decade before Jay Ward used the same gag in Dudley Do-Right. And apparently the only reason for Reddish’s name was to set up a running series of misunderstandings about horseradish.) The strip was set in the town of Mesa Trubil, “The Town Without a Country”; so wild and untameable that it had been expelled from the United States (technically, it seceded along with the rest of the South in 1861, and when the Civil War was over the U.S. wouldn’t let it back in). Mesa Trubil was ruled by Trigger Mortis and his gang (Skullface Skelly, Kit Schmit, Rockjaw Jones, No-Gun Nolan, Billy the Schnook, and Feather-Fingers Foley). For the two years of Buck O’Rue, the strip went back and forth between Buck defeating Trigger Mortis and his gang and becoming the new mayor of Mesa Trubil (supported by Dorable’s father Deacon Duncan, Doctor Proctor, Printer Winter, Gramp Gray, Sheriff Swede Kelly (with a comically exaggerated Swedish accent) and the other ‘decent element’ of the townsfolk), and Trigger Mortis’ regaining control of Mesa Trubil whenever Buck left town, or Trigger’s crooked Judge Sludge cooked up a supposed new law or a loophole in an existing law that rendered Buck legally helpless (because Buck always Respected the Law, even when it was obvious to everyone else that Trigger and his gang were making it up. One time they took advantage of the fact that Mesa Trubil had been expelled from the U.S. and demanded that Buck show a U.S. passport, which of course he did not have.).

The strip did evolve slightly over time. Buck’s girlfriend went from ‘Dorable (presumably short for “adorable”) to just Dorable. The subtitle of “… His Hoss, Reddish” was corrected to “… His Horse, Reddish”.

Even very minor newspaper comic strips deserve to be preserved. Classic Comics Press has done an excellent job. The strips (except for those annoying six missing dailies) are presented three to a page, in an attractive restored appearance that makes them look like they were photographed from printers’ proofs. The size of 1951 comic strips makes them look like enlargements compared to today’s shrunken strips. Whether you are interested in the history of American newspaper comic strips, you want a glimpse of one of the personal projects of Disney’s cartoonists, or you just want to read a slapstick Western parody, The Adventures of Buck O’Rue and His Hoss, Reddish will please you.

Disclosure: A free copy of this book was furnished by the publisher for review, but providing a copy did not guarantee a review. This information is provided per the regulations of the Federal Trade Commission.